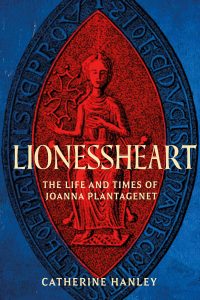

Catherine Hanley is the author of ‘Lionessheart: The Life and Times of Joanna Plantagenet’ which was published by The History Press last month.

Catherine is also the author of ‘Matilda: Empress, Queen, Warrior’, ‘1217: The Battles that Saved England’, and ‘Two Houses, Two Kingdoms: A History of France and England, 1100-1300’ amongst others.

Buy ‘Lionessheart: The Life and Times of Joanna Plantagenet:

Amazon.co.uk

The History Press

(c) Charlotte Mears

(c) Charlotte Mears

Catherine’s website – Catherine Hanley – Historian and author

Many thanks to Catherine for answering my questions.

(c) The History Press

What made you write about Joanna?

I’ve known about Joanna’s existence seemingly forever, but she only ever appears in the background of works about the more famous members of her family: as Henry II and Eleanor of Aquitaine’s daughter, or as Richard the Lionheart’s sister. She’s just another name on the family tree (and, even then, only where the family tree bothers to include the daughters at all).

Many books have been published about Joanna’s male relatives and about her mother. However, the more I read about them, the more Joanna popped up in a series of wildly different and sometimes unexpected places: in France, in Sicily, in Cyprus, in the Holy Land, in Rome … and I thought to myself, just what sort of a life did this woman lead? I therefore thought it was about time Joanna had a book of her own.

What does your book add to previous work about Joanna?

Without wishing to show off, the answer to that is ‘quite a lot’ – mainly because there has been so little written about her before, so virtually everything I came up with was new. Where Joanna makes cameo appearances in works about other people, we can find out some basic facts like what year she was born in, who her family members were, that she was the queen of Sicily, and so on, but what I hope I’ve been able to add thanks to my deep dive into the records is a lot more detail for her story.

I’m not trying to claim that I’ve somehow been able to find the definitive “real” Joanna, as that would be impossible after all this time and from the limited evidence available, but I hope I’ve been able to bring her story (as opposed to those of her male relatives) out of the shadows and on to the centre of the stage.

Was it easy to piece her life together from surviving sources?

No, it certainly wasn’t, which is presumably why nobody has ever really tried to do it before! Trying to find specific mentions of Joanna in contemporary medieval records was like looking for the proverbial needle in a haystack – huge amounts of material to sift through in order to catch a tiny glimpse of something very elusive. Most of these records were written by churchmen, who had very little to say about the deeds of women and even less interest in women’s personal thoughts and experiences. The occasional, almost throwaway, remark about Richard “and his sister” arriving at various places in the Holy Land was almost the best I could hope for.

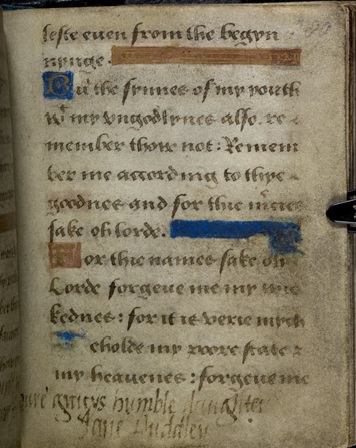

I was, however, able to find out more about Joanna herself by consulting two incredibly exciting and not particularly well-known primary sources: the only surviving charter of hers, and the full text of her will. The will was obviously composed towards the end of her life, but it gave me a huge amount of really personal information about who and what were most important to her.

It was also fascinating to get to grips with some other sources that aren’t very well known in England, for example the ones that tell us of Joanna’s time as queen of Sicily. Sicily was a very unusual kingdom in the Middle Ages: a place where Christians, Muslims and Jews all lived side by side in peace. So it was amazing to be able to bring that lesser-known aspect of history to the fore as part of Joanna’s story. That’s why I decided to subtitle the book “The Life and Times Of”, to show that she was one part of a wider medieval female experience.

How did Joanna differ from other royal women at the time?

There are some ways in which she was entirely typical of her era and class, and other ways in which she wasn’t. Her early story is exactly what you might expect: the daughter of a king, given no choice about whom she was to marry and then sent off for her wedding at a distressingly young age. But in other ways she certainly blazed her own trail. Her life in multi-cultural Sicily differed from the experiences of queens in western Europe, and then after that she went even further east, to Cyprus and the Holy Land, where she had to take a great deal of independent action, both on her own behalf and to protect others. Not many royal women were called upon to play such a role.

Is there something particular that people should know about Joanna

She wasn’t just “Henry II’s daughter” or “Richard the Lionheart’s sister” – she had an independent life of her own. And she certainly had a personality and opinions of her own, opinions that she wasn’t afraid to share!