Elizabeth Norton is the author of ‘The Temptation of Elizabeth Tudor’, ‘England’s Queens’, ‘She Wolves: The Notorious Queens of Medieval England’, as well as individual biographies about Anne Boleyn, Jane Seymour, Anne of Cleeves, Catherine Parr, Margaret Beaufort and Bessie Blount.

To buy ‘The Temptation of Elizabeth Tudor’:

Follow Elizabeth on Social Media:

Elizabeth’s website: Elizabeth Norton

Twitter: @ENortonHistory

Many thanks to Elizabeth for answering my questions.

Why did you choose this subject for your book?

It’s a fascinating story. When I first discussed the idea, many people asked me if it actually happened, it seems so unbelievable. Elizabeth is remembered as the Virgin Queen and the idea that she was involved in a sex scandal as a teenager seems improbable. Yet, it’s all true.

I also wanted to look more closely at Thomas Seymour. He is such an influential figure in Elizabeth’s life and has hitherto been poorly served with regard to biographies. He is a genuinely likeable and fascinating character, but also someone who could be highly dislikeable – a contradiction. His story is one of overweening ambition and has never really been told in detail before. The book is very much about the fall of Thomas Seymour, which was so tied up with his attempted seduction of Elizabeth.

What does your book add to existing works about Elizabeth Tudor?

It is the first time that this incident in her life has been looked at in depth. It has previously received a few pages or a chapter at most in other works. I wanted to look at everything in detail – working out where each of the characters were at any one time, as well as how they interacted and what they said.

By carrying out such a close reading of the sources relating to an episode that is widely known, it was possible to gain an entirely new perspective on Elizabeth, Thomas Seymour and Catherine Parr in the crucial few years following Henry VIII’s death.

In 1547, 1548 and 1549 Elizabeth would have had very few hopes of the throne. Although Princess Mary was likely to remain unmarried, Edward was young and healthy and likely to father children. As such, Elizabeth would have seen her future as lying in marriage – either to a member of a foreign royal family or as the wife of an English nobleman. The Seymour scandal is crucial to our understanding of Elizabeth in these years since, after Catherine Parr’s death in September 1548, his intentions turned towards marriage. The evidence overwhelmingly suggests that Elizabeth was favourably inclined towards Thomas’s suit. If his plans in January 1549 had succeeded, she might well be remembered as the wife of Thomas Seymour.

Why do you think Catherine Parr did not stop Thomas Seymour’s behaviour towards her step-daughter earlier than she did?

A lot of it lies in the status of married women in Tudor England. Catherine was, legally, entirely subject to her husband. She was supposed to obey him. Seymour was also a very complicated character. Elizabeth’s Cofferer, Thomas Parry, considered Seymour to be an ‘oppressor’ in his domestic arrangements and recounted an incident when he had flown into a jealous rage at Catherine Parr.

Catherine also undoubtedly loved Seymour and was strongly attracted to him. At first, she probably did not want to admit that anything was wrong. Later, she did take steps to ensure that Kate Ashley watch Elizabeth more closely, probably in the hope that it would quietly end the relationship. She also left Elizabeth behind at Hanworth in November 1547 when she and Seymour stayed at Seymour Place for the parliament, something which can be interpreted as a move to separate the pair. It was only when she was presented with them embracing that she finally took decisive action, recognising that matters had reached a point where it was necessary.

So, to sum up, I think Catherine tried, but her hands were tied. She also did not really want to believe that anything untoward was happening. That is not to say that she couldn’t have taken more decisive action – she certainly could – but that it was difficult for her to do so.

Why do you think Kate Ashley persisted with the idea of Elizabeth marrying Thomas Seymour, even after the scandal of Elizabeth being sent away?

Kate Ashley seems to have had something of a soft-spot for Thomas, although she was alarmed enough about some of his conduct to challenge him during Catherine Parr’s lifetime.

While there was a scandal in Catherine’s household and Elizabeth was sent away, the details were largely hushed up until Seymour’s fall. Kate later had to tell Thomas Parry, who was living in the household at the time, some of the details later, demonstrating how quietly details were kept. The Duchess of Somerset seems to have known that something was amiss, since she berated Kate for her lax supervision of Elizabeth, but there is little hint in contemporary gossip. As such, it was not particularly scandalous for Elizabeth’s name to continue to be linked with Thomas.

A marriage between the two also made considerable sense following Catherine’s death. Although Seymour was considerably older than the princess, such marriages were not unusual. As Kate pointed out to Elizabeth, Seymour was also ‘the noblest man unmarried in this land’. He was the best English match that Elizabeth could possibly make.

Elizabeth’s credit, as the product of Henry VIII’s debateable marriage to Anne Boleyn, was not particularly high abroad. She did have foreign suitors, but they were not the great princes of Europe. As such, it was possible that she would never find a foreign husband, as princesses usually did. Kate was aware of that, and probably also wanted to keep Elizabeth in England. Seymour was therefore an excellent choice. He was also charming and good looking and someone of whom Kate was very fond. It made sense that she would seek a marriage for Elizabeth to Thomas after September 1548.

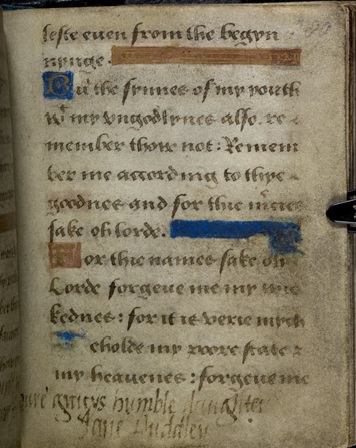

Do you agree with Janel Mueller that the prayerbook Jane used at her execution was given to her by Catherine Parr?

I think it is very likely. Mueller is, of course, an excellent scholar on Catherine Parr, and argues very convincingly that the book is written in her hand. I agree that the hand looks similar. It also makes sense that Catherine would have given it to Jane, since Jane was with Catherine at Sudeley at the end of her life.

You write, ‘Jane was tiny, even for her age. She would later be dressed in wooden platform shoes to give her some extra gravitas.’ (p.83). The description of Jane wearing wooden platform shoes comes from the letter written by Baptista Spinola on 10th July 1553. In ‘The Sisters Who Would Be Queen (paperback) and ‘Tudor: The Family Story’, Leanda de Lisle argues that the letter is a fake. Do you have an opinion about this?

Jane Grey is an absolutely fascinating character and I greatly admire the scholarship shown in Leanda de Lisle’s work on her, while I know of another historian who is also working on a biography of Jane. I have not looked into the Baptista Spinola account in as much detail as de Lisle and her argument that it is a fake does sound plausible. It is always very difficult for historians when the manuscript of a supposed original source is not extant. George Constantyne’s account of the fall of Anne Boleyn is one such source on which grave doubts are cast, while, as de Lisle has pointed out, Spinola’s is another. Richard Davey’s work on Jane is very much of its time, although to actually fabricate a source, is a rather extreme measure for a historian to go to. I would certainly now consider it doubtful. Without looking into it myself, I’m going to reserve judgment.

You disagree with other historians about the date that Jane joined Catherine Parr’s household at Chelsea. What evidence do you have for this?

We have no firm evidence for Jane’s whereabouts during most of Thomas Seymour’s marriage to Catherine Parr. For me, the evidence that she joined Catherine Parr’s household earlier than in the summer of 1548 comes from the correspondence of Elizabeth’s tutor, Roger Ascham. He joined the household early in 1548, following William Grindal’s death. In later correspondence, he wrote directly to Jane, as well as visiting her at Bradgate. His letters do suggest that he knew her well, while he was also very familiar with her tutor (whom he called ‘my Aylmer’). After Elizabeth left Catherine’s household, Ascham came with her, with the scholar complaining to a friend that Elizabeth would not let him visit Cambridge, since (as he wrote) ‘she never lets me go anywhere’. It is difficult to see how he could have become acquainted with Jane if not in Catherine’s household in early 1548.

This does not put Jane in the household any earlier than February 1548, when Ascham arrived. However, it seems probable that she would have passed to Catherine’s care following the publication of her marriage to Seymour in the summer of 1547.

Do you think that Elizabeth would have married Thomas Seymour if the Council had consented?

Absolutely and (as you will see in my book!) probably without the Council’s consent if the king agreed. Elizabeth was very strongly interested in Seymour’s suit. He was one of the most prominent noblemen in England, wealthy and closely related to the king. She was also attracted to him.

What effect did these events have on Elizabeth and did it influence her as Queen?

The Seymour scandal was hugely important in the development of Elizabeth’s persona as queen. It was the first time that we see Elizabeth taking real political action. Given how closely her name was linked with Seymour’s, she was also in considerable danger following his arrest in January 1549. I argue in the book that the Virgin Queen was born out of the ashes of Thomas’s fall. Seymour’s ambition and his death were salutary lessons to Elizabeth, which she recalled at the time of her own greatest danger during her half-sister’s reign. He was probably the man that she came closest to marrying, with his execution a reminder of the dangers of marriage.