I am delighted to host a stop on the blog tour to celebrate the UK publication of ‘Prince Arthur: The Tudor King Who Never Was’ by Sean Cunningham.

Thank you to Sean for this guest article.

Arthur and Catherine: Why a Five-Month Tudor Marriage Still Matters to British History

The marriage of Prince Arthur and Catherine of Aragon lasted less than five months. This match of two teenagers and the brief time they spent together has nevertheless become one of the most significant events of British history; but only because of the train of events it started. Those consequences could not be predicted any more than Arthur’s death, but some of the changes that stemmed from the marriage and its sudden end still resonate today.

Negotiations for the marriage in November 1501 had started even before an Anglo-Spanish treaty was agreed in 1489. Direct preparations for the ceremony and its related progress, pageants, feasts and tournaments were underway at least two years previously. Henry VII and his advisers had given themselves plenty of time to conceive and deliver the royal wedding as a spectacular demonstration of the power and magnificence of the Tudor crown. By making an alliance with Europe’s rising power, the king also indicated where his international ambitions lay.

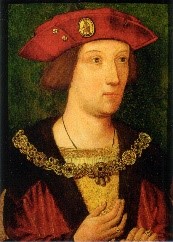

The couple who would translate this symbolism and propaganda into reality were a sixteen-year-old Spanish princess and the fifteen-year-old eldest son of the king of England. They had met for the first time on 5 November and were married only nine days later. Youthful energy had already sustained Catherine on a torrid journey that began in Spain on 17 August. She had arrived at Plymouth on 2 October but had been expected at Southampton more than a month earlier. A relentless overland journey allowed her to get to the church on time, but she had barely had a chance to adjust to what lay before her.

Against the background of state ceremonial, Henry VII’s vision of the future of the Tudor crown depended upon the relationship that Arthur and Catherine would forge. Both were highly educated and fully aware of the expectations of a semi-public life. Although the language barrier would have been difficult at first, intellectually they were better equipped than most to overcome any awkwardness that grew from suddenly being thrown together.

They had known since the age of three or four that their destiny was to be married. Surviving letters in Latin from Arthur to Catherine suggest his determination to do everything possible to welcome his bride and to love her as well as he could when she came to England. The more time they were able to spend together, the easier their marriage would become. Many factors were in favour of them establishing a happy life, but a harmonious relationship would take time to build.

Catherine and her household had been immersed in the life of the Tudor court at a highpoint of the reign. After less than two months in England, however, she and her attendants had to leave behind their brief but dazzling glimpse of metropolitan culture and head towards the Welsh Marches. Faced with the prospect of building a new life in Ludlow, it would not have been unreasonable if Catherine felt nervous. We have no information on how they got to know each other at that time, but a slow journey into the hilly Anglo-Welsh border country at the start of winter probably gave the prince and his wife some time to reflect on how their lives together would move forward.

King Henry had rebuilt the duke of York’s house, Tickenhill Place at Bewdley, as a more comfortable residence for Catherine and Arthur. That year’s feasts of Christmas, New Year, and Twelfth Night held there or at Ludlow would have been the first events over which they presided as Prince and Princess of Wales. These would have been joyous celebrations that also gave opportunities for the English and Spanish households to intermingle.

Tickenhill Place, Bewdley. A house of the earl of March rebuilt from 1499 as a comfortable residence for Prince Arthur

The early spring of 1502 was therefore surely one of the happiest periods of Arthur’s life. He had done all that his father had required of him. He was married to one of the most admired and beautiful young women in Europe. King Henry must have been overjoyed with the success of his alliance with Spain and the ceremonies that cemented it. Arthur wrote to Ferdinand and Isabella after his marriage. He expressed the joy he felt at seeing the face of his sweet bride. She was a most agreeable companion to him and he would do his best to be a good husband. The only news that would have delighted the royal parents more would have been to hear that Princess Catherine was pregnant. Twenty-five years later, whether or not the marriage was consummated at that time became the most important question in sixteenth century England.

Queen Elizabeth’s early pregnancy had been a crucial factor in improving Henry VII’s grip on the crown in 1486. For the same reason, Arthur’s marriage carried the assumption that a child would strengthen the links between England and Spain. The arrival of a baby would demonstrate the fertility of the royal couple. Equally important was the message sent by the production of heirs beyond the king’s generation. Throughout Europe, the Tudor dynasty would be seen as more sustainable as a result. At the very least, there is no reason doubt that the new royal couple, like most other teenagers, would have been curious about what was involved in making babies.

What is far more difficult to perceive is whether Arthur was physically capable of consummating his marriage. That is likely to have been the only reason on which Catherine could base her assertion that she was still a maid when she married King Henry in June 1509. There was a risk that revelation of some congenital issue might seriously damage Henry VIII’s reputation and undermine his fitness to rule. No details of her knowledge on this subject therefore emerged during the divorce investigations of 1527-8. Even at that stage of her life, Catherine was unwilling to reveal her most private information about the relationship she had with Arthur.

The strain and expectation to perform on the lavish public stage but also in private might have affected Arthur and Catherine. They had both been bred to be cool at the centre of attention. Young as they were, being a focus of the gaze of thousands of onlookers might not have been as daunting as the close physical contact they were then free to enjoy. There was no real training for dealing with such intimate situations.

The prince might be advised by people he knew that were already married, but the personal experience of meeting his future wife and then sharing a bed with her can only have been a revelation. If, as Queen Catherine later claimed, the marriage was not consummated on the wedding night, then shyness related to the awkwardness of their first time alone together was a far more likely a cause than any physical ailment afflicting the prince.

A generation later, the divorce witnesses provided bawdy and graphic detail of what was assumed to have gone on in Arthur and Catherine’s bed. At least three of them were present when Arthur emerged from his chamber on his first morning as a married man. Arthur called Anthony Willoughby over with the words, “Willoughby, bring me a cup of ale, for I have been this night in the midst of Spain”; then to all of the others present, “masters, it is good pastime to have a wife”. Willoughby assumed that Arthur was telling the truth of the previous night’s intimacies. He also said that he believed Arthur and Catherine had lain together as man and wife at Ludlow until the beginning of Lent in 1502. It is possible that this was a well-rehearsed line, designed to impress, or that it was simply very memorable in the circumstances of the happy marriage.

Other lords echoed Arthur’s high-spirits that morning. The 2nd marquis of Dorset had seen Catherine awaiting Arthur under the bedclothes the previous evening. He then noted the ‘good and sanguine’ complexion that the prince showed the next day. That was enough to convince Dorset that the marriage had been consummated. Sir William Thomas, a groom of the prince’s privy chamber, recalled escorting Arthur many times to Catherine’s door and collecting him again in the morning.

Catherine’s tutor and confessor, Alessandro Geraldini also believed that that level of contact between the newlyweds would have led to a consummation of the marriage. Mary Blount, countess of Essex and Agnes Tilney, countess of Surrey, had helped to prepare the first bedchamber that the newlyweds would share. Agnes had been one of the last to see them lying together on the night of the wedding. She was certain that Arthur and Catherine had shared a bed many times thereafter.

Some were concerned that the teenage couple would overindulge themselves in the bedroom. Catherine’s older governess, Dona Elvira, had been reluctant to let them expend their sexual energies. Henry VII, too, had at first been wary of allowing them to live fully as man and wife – preferring to send Prince Arthur back to the Welsh Marches alone, while his wife would remain in the royal household. The king was persuaded by Geraldini and the princess herself that the couple were so besotted with each other that separating them would be a cruelty that might also displease her parents in Spain.

Teenage male swaggering about sex was probably little different in 1501 to what it is now. Arthur was in the company of familiar servants and was relaying exactly the news of a successful wedding night that his friends and his parents would have expected to hear. Even if Arthur was inflating the truth of his sexual success, he still had to report that he had done his duty as a husband. Everything else being normal, his wife was unlikely to reveal any problems or difficulties at that early stage of their marriage: both would have believed that time was on their side. Unfortunately, Arthur’s death left that particular issue unresolved and dormant until it was resurrected at the end of the 1520s when Henry VIII sought to know the truth of his brother’s sexual behaviour.

Yet it is not unreasonable to suppose that two young newlyweds spending winter and spring in a relatively isolated region, with little company other than themselves, would have slept together regularly and would, probably, have consummated their relationship over five months as man and wife. Most of the memories of the aged household friends of Prince Arthur confirmed that this assumption had been widely held in 1501-02.

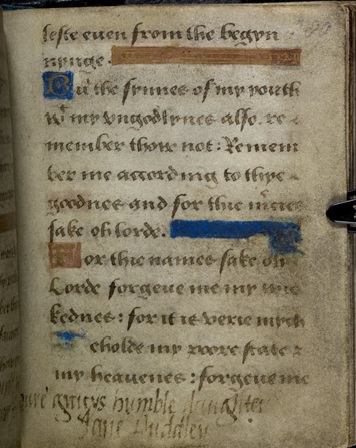

Catherine’s alternative testimony was also a powerful factor. A solemn oath carried great weight, even if she was searching her memory of events at the start of the sixteenth century. Given the intensity of Catherine’s first few months in a foreign country, it is unlikely that she would have forgotten such details. And Catherine was the only one still living who had been on the correct side of the closed chamber door in November 1501.

Despite Henry VIII’s lurid evidence-gathering, his divorce was secured without the truth of events in his brother’s marriage-bed being established. The marriage was annulled and the question became irrelevant. But by 1530, the consequences of raising it had forced King Henry to think deeply about his dead brother. When Henry examined the basis for his own marriage to Catherine of Aragon, he concluded that it was invalid because the pope’s authority was flawed. That being so, Henry knew that he would have a closer relationship with God as His direct representative within the kingdom of England. Within a few years, Henry’s belief grew into the assertive dogma that fueled the Reformation and Dissolution of the Monasteries. Its origins and its long-term consequences were found in the uncertainty over the five-month marriage of his dead brother Arthur.

Book available from Amberley, Amazon and other online outlets and bookshops.

About the Author

Dr Sean Cunningham, is Head of Medieval Records at the UK National Archives. He main interest is in British history in the period c.1450-1558. Sean has published many studies of politics, society and warfare, especially in the early Tudor period, including Henry VII in the Routledge Historical Biographies series and his new book, Prince Arthur: The Tudor King Who Never Was, for Amberley. Sean is about to start researching the private spending accounts of the royal chamber under Henry VII and Henry VIII for a new project with Winchester and Sheffield Universities. He is a Fellow of the Royal Historical Society and co-convenor of the Late Medieval Seminar at London’s Institute of Historical Research.