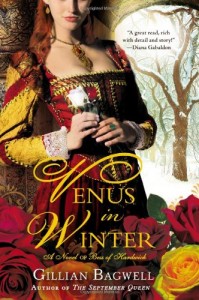

I am delighted to welcome author Gillian Bagwell to the Lady Jane Grey Reference Guide.

Gillian’s new novel about Bess of Hardwick ‘Venus in Winter’ is published on 2nd July.

Thank you to Gillian for her guest article.

Bess of Hardwick and the Tragedy of Jane Grey

In about 1545, young Bess of Hardwick, already a widow at the age of seventeen, became a lady in waiting to Frances Brandon Grey, the wife of Henry Grey, the Marquess of Dorset. Frances was nearly royalty. She was the daughter of Henry VIII’s younger sister Mary and her second husband Charles Brandon, the Duke of Suffolk. Mary Tudor wed Brandon after her first husband, the king of France, died, leaving her free to marry for love, having once married for duty.

Ladies in waiting were attendants who kept the lady of the house company and might perform such duties as helping their mistress dress, mending clothes, writing letters, providing music, or helping amuse the children of the household.

The children at Bradgate Park were eight-year-old Lady Jane Grey, her sister Katherine, who was four or five, and baby Mary, who was born in 1545. Bess became very close to the girls, especially Jane. The Greys introduced Bess to her second husband, Sir William Cavendish, and their wedding took place at the Greys’ home, Bradgate Park. Jane and Katherine may have been Bess’s bridesmaids. It was one of the most cruel twists of many in Bess’s long life that she was to see the lives of all three Grey girls end early and tragically.

Henry VIII’s preoccupation with having a male heir to succeed him is well known. He finally achieved that with the birth of his son Edward, but it was always necessary to plan for the unforeseen. The Third Succession Act restored his daughters Mary and Elizabeth to the second and third places in the succession. Henry further provided that if none of his children had heirs, the throne would pass to the descendants of his sister Mary. He excluded the heirs of his sister Margaret, and also excluded Frances Brandon, which made Jane Grey fourth in line for the throne from the day she was born.

Henry was long dead when his worst nightmare came to pass, and the son he had moved heaven and earth to get died at the age of fifteen. But Henry’s decree that Mary would succeed Edward wasn’t something that everyone in England was prepared to accept, not even young King Edward, who knew he was dying. He was very much of the reformed religion, or Protestant. Mary was Catholic, and he didn’t want to see England returned to Catholicism. So he wrote a will naming Jane Grey, who was strongly Protestant, as his successor.

Four days after Edward died on July 6, 1553, Jane Grey was proclaimed queen in London. But Mary Tudor was determined to take the crown that she believed was hers by right, and armies of Englishmen rallied to her cause. After nine chaotic days when the country teetered on outright war, the privy council changed course and declared Mary queen. Jane Grey was imprisoned in the Tower, along with others including her young husband Guildford Dudley and her father and father-in-law, and charged with treason.

Bess and her husband, Sir William Cavendish, were close friends with many of Jane’s supporters, including Jane’s parents and her husband’s parents, John Dudley, the Duke of Northumberland, and his wife Jane. William Cavendish later claimed to Queen Mary that he had raised men to support her cause, but it seems more likely that he had actually set out to help Jane’s faction, but learned that the fight was over before he got there. In any case, Bess and her husband were not among the many of their circle who were executed in the aftermath of Jane’s nine days’ reign. It was not the last time that they had to watch carefully before deciding which way to jump, when choosing wrong could mean their deaths.

Jane hadn’t really wanted to be queen, and her ambitious parents and father-in-law had more or less forced her to the throne. Queen Mary, who was close to the Grey girls and acted much like an aunt to them, likely knew that, and for a time, it seemed that she would let Jane live. Jane was comfortably housed in the apartments of one of the yeoman warders, with her own attendants. It’s likely that Bess was able to visit her there, and I have such a scene in my novel about Bess, Venus in Winter.

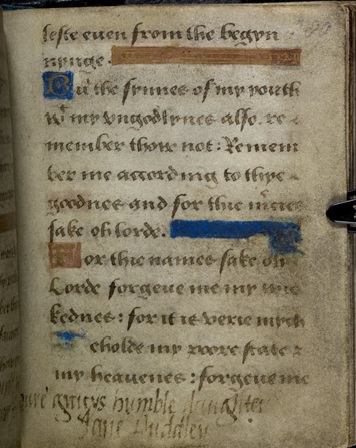

But after Mary announced that she planned to marry King Philip of Spain, many of her subjects feared that not only would England become Catholic again, but it would become nothing more than an adjunct to Spain, its existence as a country forever lost. In January 1554, Sir Thomas Wyatt led a rebellion, with the intention of making Elizabeth queen in place of Mary. Mary came to realize that as long as Jane Grey was alive, she would present a threat to Mary’s ability to hold on to the throne. On February 12, 1554, Jane’s husband Guildford Dudley was executed on Tower Hill, and Jane saw his body being brought back within the Tower walls before she was executed on Tower Green.

Bess kept a portrait of Jane Grey near her for the rest of her life, more than fifty years. And after Jane’s death, she suffered the further heartbreak of seeing Jane’s two younger sisters each take foolish and precipitous actions that ultimately lead to their imprisonment and death.

To find links to Gillian’s posts about Bess’s relationship with other subjects related to the book, please follow her:

Twitter: @GillianBagwell

Facebook: Gillian Bagwell

Website: Gillian Bagwell