‘England’s Forgotten Queen: The Life and Death of Lady Jane Grey’ was broadcast earlier this month on BBC4.

Presented by Helen Castor, it also featured ‘Jane’ historians Leanda de Lisle and Stephan Edwards.

I am delighted that they have answered my questions for a short interview about the programme.

Helen Castor

What was your favourite Jane-related document?

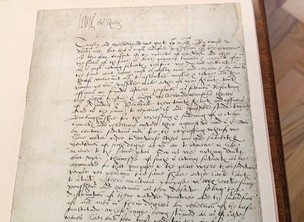

This might sound odd, given the remarkable manuscripts we were lucky enough to see, but one thing by which I was utterly ambushed was the proclamation of Jane’s accession. It’s a text I’ve read before, but the physical document – especially bound as it is into a whole volume of royal proclamations in the Society of Antiquaries – told me so much more than I’d expected. Its length, detail and density on the page, for a start: compared to the confident brevity of the proclamation of Edward VI, the anxiety about Jane’s claim was right there in its visual dimensions. And then the fact that it was so pristine; it could have been printed yesterday. Unexpectedly, I felt as transported back to the historical moment as I’ve ever done with a handwritten document.

Did you learn anything new about Jane?

There were many details of Jane’s life that talking to our contributors and retelling her story made me think about in new ways, but a fascination was following John Guy’s analysis of the well-known account of her execution, in which he demonstrates which parts were the work of an eyewitness and which were added embellishments. As so often with such discoveries, the essential evidence was already on the page: but it takes an especially keen historical eye to see it from a new angle for the first time.

What was your favourite filming location?

They’re all so different – and it’s a privilege to be given special access to such a variety of remarkable places, from galleries and archives to churches and castles – but, if I have to pick one, then I did love being out on the Thames. The river gives such a different perspective on the city, and on the water it was suddenly possible to feel the geography of Jane’s world in a way that’s no longer possible on London’s hectic streets. Plus, sitting on cushions under an awning while being rowed on a hand-crafted barge is a mode of transport I could get used to pretty quickly, given the chance.

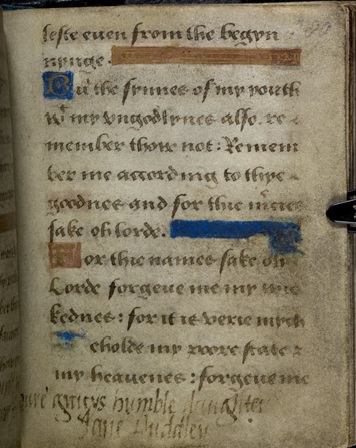

How did it feel to see Lady Jane’s prayerbook?

Again, perhaps an unexpected answer, but the emotion in the moment was relatively subdued. Of course it was beyond extraordinary to be allowed access to the tiny volume she carried in her hand on the scaffold; but we were also working against the clock to get the shots we needed and Andrea Clarke’s expertise on film, all the while making sure that nothing we did put the manuscripts with which we were working that morning (which also included Edward VI’s journal) at any possible kind of risk. So it was only really when I watched the final programme – and saw the prayerbook in its place right at the end of Jane’s story – that what I’d felt that morning, somewhere deep down, came flooding in. A physical connection across five hundred years with such an intense and harrowing moment is a profoundly powerful thing.

Leanda de Lisle

Do you think Jane is a ‘Forgotten Queen’ or is it just a good programme title?

I think she was half forgotten for a long time – and was certainly overlooked by scholars (until Eric Ives). This was why I was able to say new things about her in Sisters. Her story had become wrapped up in so many myths – and it was fun to unravel them.

What do you think this programme has added to people’s knowledge of Jane?

I hope people now see there was more to Jane than being a victim, that Mary I was a remarkable woman, that the nine days are a key period in Tudor history with long term impact.

What do you think your most important contribution to the programme was?

I think my most important role came early on – when I spoke to the researcher from the TV company – and helped explain why the Nine Days still has significance, as I was told this helped get it commissioned.

Do you think Jane should be remembered as Queen Jane?

I think Stephan Edwards got it right. She was a contested Queen, but a Queen none the less.

Stephan Edwards

Do you think Jane is a ‘Forgotten Queen’ or is it just a good programme title?

While the term does make for a catchy programme title, it is also a very appropriate descriptor for Jane Grey, on many levels. On the most literal level, I think it is accurate to say that she has been largely forgotten in the context of English and British history, despite her status as a critically important figure in the history of the Tudor monarchy and of the English (unwritten) constitution. I suspect that if you approached the average Englishman today and asked him/her to name five figures of the Tudor era, Jane Grey would seldom make the list. One would instead receive responses such as Haney VIII, Elizabeth I, Mary Tudor, Sir Francis Drake, Anne Boleyn, Thomas More, etc. And as an American, I can tell you that, on the vast majority of occasions when my fellow Americans ask me what or who I investigate as a historian, my response draws only a blank stare. But I suspect that Jane is also largely forgotten in the sense that, even if people recognize the name, they most often cannot give an accurate indication of her place in Tudor or English history. They may know that she existed but not who she was or what she did.

From my own perspective, Jane has until recently been entirely forgotten by academic historians. As I have said so very many times over the years, when academic historians mention Jane Grey at all, it is usually only exceedingly briefly, and that mention often relies heavily on the posthumous mythology (e.g. the Spinola letter) rather than the primary sources. One thing I think the programme went a long way towards accomplishing was the setting aside of that mythology and attempting to restore Jane to her rightful, primary-source-based place in Tudor English history.

What do you think this programme has added to people’s knowledge of Jane?

Again, I think the programme went a long way towards restoring Jane to her rightful, primary-source-based place in history and towards dispelling some of the more egregious portions of the mythology. If I had to choose one aspect of that mythology that I was most grateful to see the programme correctly address, it was the myth that Jane was a weak and simpering child-victim who was totally innocent in the events of July 1553. I think the programme did a remarkable job of making it clear that Jane was fully capable of understanding what was happening around her and of asserting herself when she felt that it was imperative to do so, and that like her cousins Mary and Eliabeth Tudor, she too had a practical understanding of politics and was capable of decisive action.

What do you think your most important contribution to the programme was?

In all honesty, I think my greatest contribution took place largely off screen. Beginning in May of 2017, the production team and I were in almost daily contact regarding the development of the three episodes. Lucie Crawford at Darlow Smithson Productions, in particular, sent me emails or called on Skype with regularity for guidance towards the best primary sources suitable for filming, for fact checking, and even for answers to basic questions. I know Ms Crawford did the same with Leanda de Lisle and others, so I cannot take sole credit in this area. But I was certainly grateful, as the only historian fully trained and experienced in academic historiographical methodologies, to have had the opportunity to provide input behind the scenes during the development process.

Do you think Jane should be remembered as Queen Jane?

This is a very difficult question, and your readers will have to forgive me if I directly contradict my answer to a similar question posed toward the end of episode three. In the relative isolation of filming the interview, I argued that Jane did actually reign for those nine days in July 1553 and that she did so with the acquiescence of a majority of the political elite, requiring us today to number her among the monarchs of England. But after seeing myself making that argument on-screen and within the larger context of the three episodes, I was forced by the other excellent content of the programme to reconsider my position. One aspect of the succession crisis that the programme makes patently clear, and a point that I have long argued myself, is the extent to which Jane had so very little support from among the common people. The entire succession problem was, at its core and as I have argued before and elsewhere, a challenge to the unwritten English constitution and that constitution’s definition of monarchical legitimacy. That is, the succession crisis asked the fundamental question, “What makes a person a king or queen?” The outcome of the succession crisis provided an unambiguous answer: “The people do.” A person may inherit the crown through birth, or they may seize it by military force, or they may be placed there (as Jane was) by a relatively small coalition of the political elite, but ultimately it is up to the citizens of the realm to determine who will or will not rule over them. Monarchical legitimacy arises from the consent of the governed. That fact is made clear in the coronation ritual, which begins in its modern form with the Recognition. The assemblage is asked by the officiant, not once but instead four times, “Sirs, I here present to you your undoubted King/Queen. Wherefore all you who are come this day to do your homage and service, are you willing to do the same?” In modern English, “Here is the person who is to be your monarch. Do you accept him/her as such?” Though Jane was never presented at a coronation ritual for recognition, the people of England made it abundantly clear through their silence at her public proclamation of accession on 10 July 1553 that they did not so recognize her as their rightful monarch. For the first time in relation to an English monarchical succession, the will of the common people overruled not only the will of the political elite, but also the explicit wishes of the recently-deceased previous monarch. The overwhelming majority of the common citizens of England in 1553 did not wait for the Recognition portion of any future coronation ritual, but instead pre-empted the process by flocking to Mary in a physical show of support. The people acted of their own accord to make Mary their legitimate monarch, totally dismissing and negating in the process any legal, political, or cultural arguments to the contrary. If kings and queens are made through the consent of the governed, then I regret to say that Jane must remain known in history as simply Lady Jane Grey Dudley, not as Queen Jane.