I am delighted to host this guest article to celebrate the publication of ‘The House of Grey: Friends & Foes of Kings’ by Melita Thomas.

Thank you to Melita for this guest article about Lady Jane and her father.

Father & Daughter

Almost any discussion of Lady Jane Grey will centre on the idea that Jane was the victim of the ambitions of powerful men – particularly her father-in-law, John Dudley, Duke of Northumberland, but also her father, Henry Grey, Duke of Suffolk. What, we ask ourselves, can Suffolk possibly have been thinking to put his daughter in such a position? And worse, once the initial attempt to enthrone her had failed, what madness took hold of him to join Wyatt’s inept rebellion?

The conventional answer is that Jane was nothing to her father but a tool for his ambitions, that she was bullied by both her parents, that nothing she could do was ever good enough and that she received ‘nips and pinches’ whenever she stepped out of line. But is this a fair characterisation of her relationship with her father?

My research for the House of Grey has led me to believe that Jane’s relationship with Suffolk was much warmer and gentler than is usually portrayed, and that, whilst Jane’s youth and gender did make her a victim of others’ plans, she was not necessarily being driven in a direction she did not like.

There is limited evidence of Jane’s early childhood, but we can confidently say that her father, who was a man of learning himself and patronised scholars, particularly those of the Reformed faith, was eager for his daughter to have the best possible education. His reasoning was probably two-fold. First, Jane’s spiritual health: the ability to read the Word of God in the original Greek and Hebrew was highly prized by the reformers and Bible study was at the centre of Jane’s learning. Second, from the time that Jane was ten, in 1547, Suffolk hoped that she might marry the young king, Edward VI.

Edward was being brought up as a child prodigy, with a firmly Protestant religious outlook, and a similar education for Jane would make her a suitable bride – far better than the other options suggested for Edward – Mary, Queen of Scots, or Elisabeth of Valois, both Catholic. Suffolk had not come up with this scheme by himself – he was a suggestible man, easily led, and had fallen under the influence of Sir Thomas Seymour, the Lord Admiral, brother and rival of the Lord Protector, the Duke of Somerset. Seymour, who resented his brother’s position was seeking to build his own route to power. He was courting the dowager queen, Katherine Parr, and he persuaded Suffolk (who was still only Marquis of Dorset at the time, but will be referred to as Suffolk for simplicity) that if he was sold Jane’s wardship and marriage, Seymour would be able to secure a match with Edward. This sounds heartless, but such arrangements were not unusual. Seymour was also willing to pay the perennially-broke Suffolk handsomely – a sum of £2,000 was agreed.

At the time the deal was made, the Suffolks were living in their London home of Dorset House so Jane and her tutor, John Aylmer, were easily transported to Seymour Place. Although Seymour had perhaps married Katherine Parr by this time, he was still officially a bachelor, so it is likely that his mother, Lady Seymour, was draughted in to supervise the little girl. Even after the marriage between Katherine and Seymour was made public, Jane remained at Seymour Place, although she visited Katherine from time to time. Suffolk visited Seymour Place regularly – partly to continue intriguing with the admiral, but also to see Jane. With no companions of her own age, Jane would have had little to do but study – but this was no hardship for her.

In the late spring of 1548, a pregnant Katherine Parr retired to the admiral’s castle at Sudeley in Gloucestershire, and Jane accompanied her. Katherine, like Suffolk, was an eager follower of the Reformed faith, and Jane was influenced by Katherine’s own religious writings and also by Katherine’s chaplain, Miles Coverdale. Coverdale, despite having contributed to the translation of the bible that became the Great Bible, mandated for use by Henry VIII, had become too radical for Henry to stomach, and had gone into exile in Strasbourg, returning with Calvinist convictions that Jane absorbed.

Queen Katherine died in childbed in early September 1548. Within a few days, Seymour wrote to Suffolk that he intended to break up the household and send Jane back to her father as he was the person who would be ‘most tender on her’. This concern for his ward’s emotional well-being is one of the few redeeming features in Seymour’s career. Suffolk was making preparations for Jane’s return, when another letter arrived at Bradgate. Seymour had changed his mind and intended to retain his late wife’s household to care for their baby, under the supervision of his mother. He wanted Jane to stay with him.

Suffolk acknowledged Seymour’s affection for Jane and his ‘good mind’ towards her education but declined the offer. It would be better for her to be in her mother’s care. His reasons sound rather grim to modern minds. Jane should be with someone who could ‘correct her as a mistress, and monish her as a mother’. He seems to have been rather concerned that Seymour was spoiling his daughter. If she remained with him, being of ‘tender years’, she might

‘for lack of a bridle take too much the head and conceive such opinion of herself that all such good behaviour as she heretofore has learned by the queen’s and your most wholesome instructions should altogether be quenched in her or at the least much minished’,

But whilst this sounds strict to us, it shows a high level of care for his daughter, within the norms of sixteenth century behaviour. For anyone, particularly a young woman, to grow up lacking discipline and proper humility would imperil not just their material position in the world, but also their spiritual health. Suffolk’s concern for Jane was genuine. Jane’s mother, too, wanted her at home. She wrote to Seymour promising that whilst she would be happy to continue consulting him about Jane’s welfare, she wanted her daughter at her side – her letter also hints that she did not want Jane to marry too young.

Suffolk insisted on Jane’s return and sent an escort to fetch her from Sudeley. Jane’s own opinion cannot be known for certain. She wrote Seymour a polite letter, thanking him for his ‘great goodness’ towards her and acknowledging that he had behaved towards her as a ‘good and loving father’, but the letter is a conventional one of thanks, and it is unlikely she wrote it without Frances supervising her.

It was not long before Seymour followed Jane to Bradgate, accompanied by his friend, Sir William Sharington, to help him persuade Suffolk to let Jane return. Sharington worked on Frances whilst Seymour used all his powers of bullying and persuasion on Suffolk – including £500 of the promised loan of £2,000, and, once again, the hopes of marriage to the king. That Suffolk could have been persuaded there was any chance of such a match indicates both Seymour’s silver tongue, and his own lack of political sense. Nevertheless, from the perspective of a sixteenth century father, the opportunity for Jane to be a queen could not be resisted – especially as her attachment to the Reformed faith, which she now embraced as whole-heartedly as himself, would benefit the kingdom. Jane was permitted to return to Seymour’s care. Suffolk took her to London himself, and remained in the capital, visiting her frequently at Seymour Place.

Seymour’s behaviour over the winter of 1548-9 became so extreme that, by the end of January, his brother, the Duke of Somerset, believed he had no option but to arrest him. Suffolk was questioned and admitted the plan to marry Jane to the king. He was persuaded by Somerset to give up the idea, and to agree to a marriage between Jane and Somerset’s oldest son, Edward, Earl of Hertford, instead.

Convicted of treason, Seymour was executed in March 1549. His hopes of her advancement dashed, Suffolk took Jane back to Bradgate. They stopped en route in Leicester, where both father and daughter received gifts of wine from the council and the mayor’s wife.

By 1549, it seemed clear that Suffolk and Frances would have no more children. With no son, Suffolk put all his hopes in Jane. She continued to receive the best possible education, and Suffolk encouraged her to write to the continental reformers, particularly Heinrich Bullinger. The Bishop of Gloucester, Hooper, described Suffolk as ‘pious, good and brave and distinguished in the cause of Christ’, although the Imperial ambassador painted a less-flattering portrait, calling him a ‘senseless creature’. Jane shared her father’s convictions, and in 1551 John of Ulm, another European reformer, whom Suffolk supported financially, called her ‘pious and accomplished beyond what can be expressed.’

Nevertheless, it is to this period that Roger Ascham’s sad portrayal of Jane’s family life, that has become legendary, pertains. Ascham was tutor to Jane’s cousin, the Lady Elizabeth and some thirteen years later wrote a treatise entitled The Schoolmaster, intended to promulgate his unusual view that the best method of teaching was by positive reinforcement, rather than punishment. To illustrate this theory, he contrasted Jane’s relationship with her schoolmaster, who had followed this style of teaching, against that with her parents. He had come upon Jane at home, reading a Greek book, he wrote, whilst the rest of the family was out hunting. She told him she loved learning, because it gave her respite from her parents. He quoted her as telling him that ‘One of the greatest gifts God ever gave [her], [was]that He sent [her] so sharp severe parents and so gentle a schoolmaster.’ At the time, in a letter he wrote to Jane shortly after the visit, he only complimented her extravagantly on her brilliance, and the pride of her parents and schoolmaster in her attainments.

That Suffolk was strict with Jane does not mean he did not care about her – rather, in the sixteenth century context, the reverse. To spare the rod, was to spoil the child. That Jane had a tendency to teenage rebellion would not have come as a surprise to her parents. Although the term ‘teenager’ was not known, the concept of adolescent restiveness and chafing against parental authority was familiar. Indeed, Suffolk’s concerns in his letter to Seymour suggest that even at twelve, Jane was of a strong and determined character. It was his duty to help her manage herself.

Jane turned sixteen in 1553, probably in May. On 25th May she was married. Much ink has been spilt on whose idea the marriage was, whether her parents were of one mind on the matter, whether they were bullied into it, and how Jane herself felt about her new husband, Lord Guildford Dudley, who was certainly a come-down from the proposed marriage to Edward VI. Guildford’s father, the Duke of Northumberland, had supplanted the Duke of Somerset as the leading man in the kingdom during Edward VI’s minority.

Like Jane and Suffolk, Guildford was a firm follower of the Reformed faith, so Jane can have had no objections on the score of religion. Whether they were personally compatible is unknown. Romantic Victorian writers saw a doomed love-story, whilst modern historians tend to believe Jane was married against her will, but there is no proof either way. Certainly, sixteenth century young people were expected to accept their parents’ choices and love their allotted spouse.

Whether Suffolk was initially in favour of the match or not, it soon became apparent that there was a wider scheme afoot – to place Jane on the throne, rather than the king’s half-sister, Mary, when Edward died, which, everyone knew in the summer of 1553, could not be long. Why did Suffolk agree to the scheme? With the benefit of hindsight, it seems that the plan was doomed. Jane was unknown by the populace and her marriage to Guildford was unlikely to recommend her – Northumberland was widely disliked. Mary was an adult, the heir under the Act of Succession of 1544 and Henry VIII’s will, she had the backing of vast landholdings in East Anglia and was extremely popular.

At the time, however, things may have appeared differently. Northumberland had control of the king and council and Edward himself was eager for Jane to succeed him to continue the development of Protestantism in England, which he feared that Mary, who adhered to the old faith, would undo. Suffolk’s motivation was, of course, in part, ambition. To be father of the queen, whom no doubt everyone thought would be obedient to her menfolk, would be to reach the summit of society. But his genuine religious faith was also a factor. He had supported the Reformed faith for at least ten years – his was not an overnight conversion, but a deeply held conviction. Whilst nobody could be sure that Mary would reverse all the religious changes of the previous twenty years, no-one doubted that she would return the country to the state of religion as it was at the death of Henry VIII – essentially Catholic in doctrine.

For Suffolk and Jane, this would be a disaster, not just for them, but, they thought, for the souls of the people. These convictions, together with his personal inability to stand up to stronger characters, made Suffolk Northumberland’s willing support. He probably also thought the risk was low – there had not been a successful rebellion against the central authority in England since the accession of Henry VII in 1485. With the support of Northumberland, Suffolk and the other Privy Councillors, many of whom were linked to both men by marriage or blood, the plan seemed certain of success. Suffolk would probably have preferred a more conventional appointment of his wife as Edward’s heir. Had Frances been nominated, Suffolk would have had the title of king, and been likely to hold more sway – it being assumed in the sixteenth century that female heirs would be strongly influenced by their husbands. The very fact that Frances was overlooked indicates Northumberland’s personal motives – by supporting Jane’s claim, Northumberland could hope to continue in power by manipulating her through Guildford.

Jane was informed that Edward had nominated her as his heir. Shocked at the news, she asked her mother-in-law for permission to visit her parents. The duchess refused. Jane chose to disobey and to visit Suffolk and Frances anyway. This is surely an indication that, far from dreading her parents, Jane turned to them for support when confronted by the astonishing news. Presumably reassured by her parents, Jane returned to her spousal home, and, it appears, went to Chelsea Manor with Guildford, perhaps comforting herself with the thought that Edward might live for many years, and have an heir of his own – his deteriorating health was being kept as secret as possible.

But Jane had barely had time to reconcile herself to the idea that one day she might be queen, when messengers arrived from either Northumberland or Suffolk, to convey her to the Northumberland property at Syon, where she was informed that Edward had died, and she was to be queen. According to her own account, Jane protested vigorously that Mary was the true heir, but she was persuaded by her parents, her in-laws and the rest of the councillors present that it was her duty to accept the charge that the late king had laid upon her.

Her initial reluctance overcome, Jane prepared to be the best queen she could be – which meant a queen dedicated to promulgating Protestantism in her kingdom, and defeating the ‘papist’ Mary, as Jane’s first proclamation described her cousin. It was soon apparent that defeating the opposition would be much harder than Northumberland and Suffolk had anticipated. Mary was raising an army, and it was vital that the government’s forces should be mobilised to resist. Who could be better to lead Jane’s troops than her ‘own loving father’? At first, Jane agreed, but Suffolk, prompted by Frances, declined, pleading illness. Jane was persuaded that he should remain with her, so there was no alternative, her councillors decided, but to send Northumberland himself. He, too, was reluctant – aware that his fellows were neither so committed to the coup, nor so resourceful in managing a difficult situation. Certainly, Suffolk had none of Northumberland’s political skill, nor his domineering personality.

Northumberland set out, whilst Suffolk and Frances remained in the Tower with Jane. But before long, dire news was received – Mary’s support was swelling dramatically, and many of the privy councillors were finding excuses to slip away from Jane and declare their allegiance to Mary. Suffolk tried to prevent further losses by ordering the Tower gates to be locked each day and the keys brought to Jane for safe-keeping, but neither father nor daughter had the authority to prevent support leaching away. A body of councillors, informed that Mary was likely to raise a force that could not be overcome, ordered the Lord Mayor to proclaim her as queen. A delegation came to the Tower to inform Suffolk that Jane’s ‘reign’ was over, leaving the unpleasant task of telling her, to him.

Suffolk entered his daughter’s chamber and told her that she was no longer queen, taking down the cloth-of-estate with his own hands. In probably the most reprehensible act of their entire lives, Suffolk and Frances left the Tower without their daughter – leaving her to her fate alongside her husband and mother-in-law. The only possible argument in their favour may be that they thought Queen Mary would be more likely to be merciful to her young cousin, if she appeared to be alone. As it transpired, Mary did indeed accept Jane’s assurances that she had been prevailed on to take the crown against her own will. Suffolk was pardoned, at the urging of Frances, and Jane, although she and Guildford were found guilty of treason, was treated honourably in the Tower, Mary refusing to accept advice to have her executed.

Suffolk could have accepted his lucky escape from the axe that dealt with Northumberland, kept a low profile, and waited for Jane to be released, but his zeal for his religion would not allow him to accept Mary’s return to Catholicism. In November 1553, he aggravated the queen by objecting in the House of Lords to the restoration of Catholic services, and then angered her further by disputing her choice of husband.

Suffolk was not the only one to object to Mary’s decision to marry Philip of Spain. Before 1553 was out, rebellion was being plotted, principally by Thomas Wyatt, and Suffolk was soon involved. It seems unlikely that he anticipated the restoration of Jane – more likely that he hoped either to prevent the marriage, or see Mary replaced with Jane’s other cousin, the Lady Elizabeth, who, although by no means the ardent Protestant Jane was, had religious views more to Suffolk’s mind.

In his support of Wyatt, Suffolk once again showed either his lack of political judgement or his overwhelming devotion to Protestantism. He must have known there was a high risk the revolt would fail, and, even if he thought it unlikely Jane would suffer by his actions because she was not involved, he must have realised there was a risk that the sentence of death hanging over Jane would be implemented. The only explanation for his behaviour is that he believed, and knew that his daughter also believed, that to risk martyrdom for the sake of their faith was a noble and glorious act, and that they would meet again among the Elect in paradise.

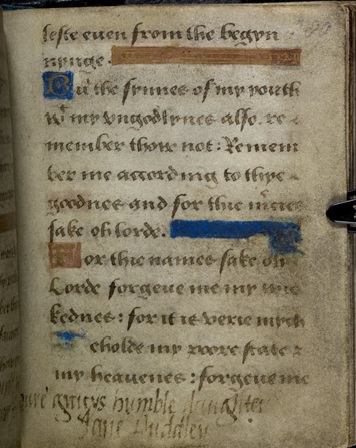

He made for Leicestershire, where his attempts to raise the country against the queen fell flat. He was arrested by an old friend, a man who shared his faith, but not his political ineptitude – the Earl of Huntingdon. Despatched to the Tower, Suffolk soon heard that Jane and Guildford, having refused to accept Catholicism, were to be executed. There is a letter that purports to be from Jane to her father, blaming him for her situation, but this is believed by modern historians to be a forgery. The only certain message from Jane to her father in these last fraught days, are the words written in the prayer-book that was shown to him after her death. The words suggest a love and respect for her father, and a sharing of religious ideals that is far from the picture of an unloved and bullied child:

‘The Lord comfort your grace and that in His word wherein all creatures only are to be comforted. And though it hath pleased God to take away two of your children, yet think not, I most humbly beseech your grace, that you have lost them, but trust that we, by leaving this mortal life, have won an immortal life. And I for my part as I have honoured your grace in this life, will pray for you in another life. Jane Dudley’.

Buy ‘The House of Grey’:

Amazon.co.uk

Amberley Publishing

About the Author

Melita’s first book, ‘The King’s Pearl: Henry VIII and his daughter Mary’ was published by Amberley in 2017.

Melita is also the co-founder and editor of Tudor Times, a repository of information about Tudors and Stewarts in the period 1485-1625 www.tudortimes.co.uk.

Follow Melita and the Tudor Times on Social Media

Tudor Times: Tudor Times

Facebook: Tudor Times

Twitter: @thetudortimes