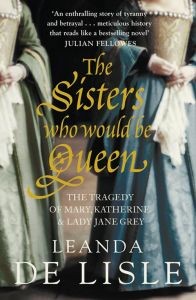

Stephen Jakobi attended Leanda de Lisle’s talk last weekend and has very kindly allowed me to post his notes.

Notes on a lecture given by Leanda De Lisle,

The New Walk Gallery, Leicester 25th of January 2009

Leanda De Lisle commenced by stating that she was first interested in writing about Katherine and Mary and thought there would be little new to write about Jane. As research for the novel carried on and she went back to primary sources, she realised that much that had been written about Jane was not true and went on a mission to peel back myths.

Examples include:

The Frances Grey effigy on her tomb had disclosed that she was a slim, elegant woman.

It was clear from her own research that Jane was born in any event before the end of May 1537, and that Jane’s traditional ‘twinning’ with Edward VI was a myth.

It was most unlikely that Jane was born at Bradgate, because it was then inhabited by Frances’s mother in law, who was on bad terms with Henry Grey. The ‘Dragon’ remained in her lair until January 1538, when Henry succeeded in evicting her.

It was reported that Jane was small, with reddish hair and freckled skin. Certainly bright and feisty and had frequent rows with her parents. Katherine was pretty, charming and affectionate-a romantic animal lover. Mary was no beauty. “The shortest person at court”, but bright, loving and affectionate.

By Henry VIII’s will, as authorised by Parliament and statute, the Stuart line was excluded and the Grey girls became heirs.

In 1553, Edward VI became gravely ill, and wrote his own will (Device for the succession). He excluded his half sisters and gave Frances governance of the Realm until she or one of her daughters had a son. It was therefore important to marry off the Grey girls and get them breeding.

It was the wife of William Parr, the Marquis of Northampton, who made the suggestion that Jane be married to Guildford, and Katherine to the son of the Earl of Pembroke.

The suggestion that in Tudor times girls reached adolescence early was untrue; one only had to look at the diet. 12 then was the equivalent of the modern 10.

When Jane’s marriage had been consummated, Edward made a small change to his will at the suggestion of Sir John Gates. The Crown was to pass directly to Jane. Frances was called to the dying boy’s bedside but the conversation was unrecorded.

Jane’s recorded statement, when she was given the news of Edward’s death that she did not wish to be Queen was more in the nature of a public statement that she would rule to God’s glory.

In the formal procession on the following day to the Tower there was a noted absence of enthusiasm from the common people. Mary was made of sterner stuff than expected. Mary proclaimed in the Eastern counties and civil war loomed.

Jane ordered Northumberland to lead her forces, unwilling though he was because the councillors were uneasy and he feared their defection. Nevertheless, he agreed to leave London at the head of the army. Defections started and by July the 19th Jane’s reign ended. London was delighted.

Mary hoped to pardon Jane, but Northumberland was beheaded in August. In November Jane was tried for treason, but believed she would be pardoned.

It was then that Jane wrote an open letter demanding that people resist the Catholic Mass (introduced in December).

Her Father plotted to overthrow Mary, but the date for the uprising, originally Easter 1554, had to be brought forward because of leaks.

When the Wyatt rebellion commenced in February, Mary actually requested Henry Grey, whilst he was at his London residence, to lead her army. But instead he slipped away to raise a standard for the rebellion in Leicestershire. Wyatt succeeded in getting to the gates of the City and Jane could hear sounds of battle.

Mary was immediately persuaded to execute Jane, who heard the news and was frightened but brave.

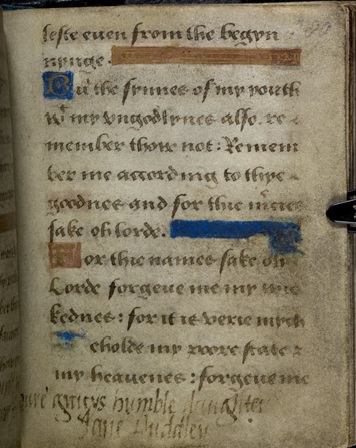

Jane decided she was going to die a martyr’s death and wrote propaganda letters for publication. The Letter to her father tried to escape the traitors tag and make her seem an untarnished martyr and the letter to her sister, telling her to seek death rather than compromise belief. She behaved courageously at her execution, made a great speech.

Leanda De Lisle ended by outlining the very romantic stories of Katherine and Mary.