May 25th last year marked the 462nd anniversary of the marriage of Lady Jane Grey (who was Queen of England for nine days in 1553) to Lord Guildford Dudley. There are various accounts relating to Jane’s wedding and this article looks at some of those featured in Richard Davey’s ‘The Nine Days’ Queen: Lady Jane Grey and Her Times.’

Published in 1909, the biography contained the only detailed, contemporary description of Queen Jane’s arrival at the Tower of London on 10th July 1553. Davey claimed that the description was written in a letter by Baptisa Spinola. The authenticity of this letter and its description of Jane have been questioned since late 2009, by historian Leanda de Lisle. De Lisle has concluded that the letter is a fake. (1)

Research into this letter and other claims made by Davey has also been conducted by Dr Stephan Edwards. He writes that, ‘Davey published his first version of the letter in 1906 in The Pageant of London.’ (2) Edwards describes how ‘Davey’s Nine Days’ Queen contained numerous other obvious fabrications developed to fill documentary voids.’ (3) I investigated some of these in an article in the February 2015 edition of ‘Tudor Life Magazine.’ (4)

Davey describes how Jane was forced to marry by her parents, the Duke and Duchess of Suffolk. He writes:

‘About a week before the wedding her parents ordered her to marry the young gentleman, and, according to Baoardo, she at first stoutly refused, “her heart,” she said, “being plighted elsewhere.” The Duke harshly reiterated his command and, according to the Italian chronicler, even struck his daughter several hard blows, whilst the broad red face of the Lady Frances purpled threateningly.’ (5)

Davey gives his source as ‘Baoardo, a Venetian who was in England in 1553-6, wrote a historical pamphlet on the events he beheld.’ (6) Edwards writes that authorship of this account (Historia delle cose occurse nel regno d’Inghilterra ) was claimed by Giulio Raviglio Rosso (7) and that it was misattributed to Frederico Badoaro by several nineteenth century historians (including Davey). (8) This was ‘because his is the first personal name to appear in the work’ and that they ‘assumed Badoaro (misspelled by all as ‘Baoardo’) to have been the actual author of the volume, despite Rosso’s clear – though later – assertion that Badoaro had only read and approved of the work.’ (9)

In this translation of Rosso’s work by Edwards, he writes:

‘And with this intention he determined to give his third son to the first born of the Duke of Suffolk, named Jane. The which [was] that she might even much refuse this marriage, nonetheless, and urged by the mother, and beat by the father, she was required to content herself,’ (10)

There are several other sources that state that Jane was physically compelled to marry Guildford. The earliest account according to Eric Ives (writing in 2009) was from the papal official, Giovanni Francesco Commendone. Ives writes that Commendone ‘arrived in London on 8 August and was back in Rome by 8 September.’ (11) So, the earliest that Commendone could have heard of this, was the first week of August 1553. Commendone wrote in his 1554 account ‘Events in the Kingdom of England,’ ‘And he made arrangements to marry his third son to the first-born daughter of the Duke of Suffolk, Jane by name, who although strongly deprecating such a marriage, was compelled to submit by the insistence of her Mother and the threats of her Father.’ (12)

Since the publication of ‘Lady Jane Grey: A Tudor Mystery’ in 2009, two new letters have come to light, one of which (dated or written on 24th July 1553) mentions Jane’s wedding. The letters were discovered by Stephan Edwards in 2013 and appear in the third volume of ‘Lettre di Principi’, which he describes as ‘a series of a collection of letters to, from, or about a wide variety of early-sixteenth-century European rulers, noblemen and princes of the Roman Catholic Church’ which was published in 1577 by Giordano Ziletti. (13) According to Edwards, the author and recipient of the letters are unknown but he thinks that they were written by a member of the Venetian diplomatic embassy. (14)

‘The Duke of Suffolk, Jane’s father, was persuaded of it, and overcome by the inducements and effective methods of this man. But the Duchess of Suffolk with all her household would not have wished [it], and the daughter was forced there by the father, with beating as well.’ (15)

As noted by Leanda de Lisle, this letter changes the date of the first recorded mention of Jane being forced to marry, to the 24th July 1553. (16) Also we have seen that both Commendone and Rosso reported that the Duchess supported the match. De Lisle writes that, ‘One of the many fascinating things in the new Italian letters discovered by Stephan Edward is that the first of these, dated July 24th 1553, describes how Frances opposed her daughter’s marriage to Guildford.’ (17) This view is also reported in Wingfield’s ‘Vita Mariae’, which according to Ives, is the ‘earliest English account’ of events of July 1553. (18)

‘The timid and trustful duke therefore hoped to gain a scarcely imaginable haul of immense wealth and greater honour of his house from this match, and readily followed Northumberland’s wishes, although his wife Frances was vigorously opposed to it…’ (19)

At the time Davey was writing this biography, there was one source (Wingfield) that stated that Frances had opposed the match and at least two (Commendone and Rosso) that said she supported it. So while Davey was not incorrect, according to his source, in stating that Frances wanted Jane to marry Guildford, we cannot know if ‘the broad red face of the Lady Frances purpled threateningly.’ (20) By describing Frances in this way, it could be argued that Davey is contributing to what de Lisle calls the ‘slandering of Frances’s reputation.’ (21)

Although Davey writes that ‘No contemporary account of this particular ceremony is in existence’, (22), his biography includes a description of what Jane wore on her wedding day. Davey copies the description from Burke’s ‘Tudor Portraits’ (published in 1880) but does state that Burke does not name his source. (23)

‘Lady Jane’s headdress was of green velvet, set round with precious stones. She wore a gown of cloth of gold, and a mantle of silver tissue. Her hair hung down her back, combed and plaited in a curious fashion ‘then unknown to ladies of qualitie.’(24)

None of the contemporary accounts of Jane’s wedding include a description of what the bride wore. Eric Ives notes in ‘Lady Jane Grey: A Tudor Mystery’, that ‘English observers do not mention the celebrations.’ (25)

News of and details of the wedding do appear in the despatches of the Imperial Embassy and in one of the newly discovered letters from a member of the Venetian embassy. The Imperial Ambassadors do not describe Jane, although they reported on 12th May 1553 that ‘The King has sent presents of rich ornaments and jewels to the bride.’ (26) and on 30th May that ‘the weddings were celebrated with great magnificence and feasting at the Duke of Northumberland’s house in town.’(27)

The Venetian embassy letter mentions that Jane did not dine in public on one of the days of the celebration and that ‘the wedding was conducted with such splendor that I have not seen anything similar in this kingdom,’ (28) but gives no description of what Jane wore.

Ives writes that ‘the earliest evidence of Jane’s betrothal to Guildford is a warrant dated 24th April 1553 to deliver ‘wedding apparel to the bride and groom, their respective mothers and also the lady marquis of Northampton.’ (29)

John Strype describes the warrant, ‘And for the more solemnity and splendour of this day, the master of the wardrobe had divers warrants, to deliver out of the King’s wardrobe much rich apparel and jewels: as, to deliver to the Lady Frances, Duchess of Suffolk, to the Anno 1553. Duchess of Northumberland, to the Lady Marchioness of Northampton, to the Lady Jane, daughter to the Duke of Suffolk, and to the Lord Guilford Dudley, for wedding apparel; (which were certain parcels of tissues, and cloth of gold and silver, which had been the late Duke’s and Duchess’s of Somerset, forfeited to the King;).’ (30)

As Burke gives no source for his description of Jane (31), if he wrote it himself, it is likely that he was influenced by the details given in the royal warrant. Therefore it is possible that Jane wore garments made from these materials, but we have no contemporary description to prove it.

Davey’s account of the wedding also includes a physical description of Jane. He writes that ‘the bride was considered pretty, but small and freckled.’ (32) The only mention of Jane being ‘small and freckled’ is in the Spinola letter, which as stated earlier, is considered to be a fake by both de Lisle and Edwards. ‘This Jane is very short and thin, but prettily shaped and graceful…I stood so near Her Grace, that I noticed her colour was good, but freckled.’ (33)

Contemporary accounts of Jane arriving at the Tower, from her captivity, her leaving the Tower for her trial and her execution, do not describe her physical appearance in terms of what she looked like. From accounts of Jane’s arrival at the Tower, the most we know of Jane’s appearance is that her mother, carried the train of her gown. (34)

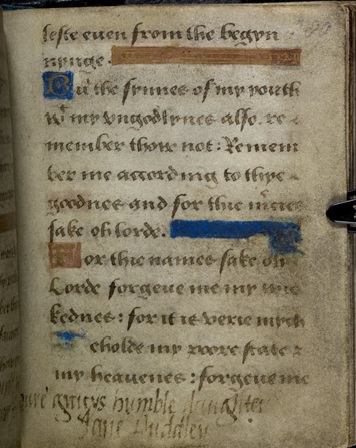

The author of ‘The Chronicle of Queen Jane and Two Years of Queen Mary’ describes the dress Jane wore to her trial, ‘The lady Jane was in a blacke gowne of cloth, tourned downe; the cappe lined with fese velvet, and edget about with the same, in a French hoode, all black, with a black byllyment, a black velvet boke hanging before hir…’ (35)

The description of his dinner with Jane on 29th August 1553 does not include any details of her appearance (36) and the only comment about Jane’s appearance on the day of her execution, was that she wore ‘the same gown wherein she was arrayned.’ (37)

The newly discovered letter from 24th July 1553 includes an opinion about Jane’s appearance, ‘The first-borne daughter of the Duchess of Suffolk is a pretty and comely young lady of beautiful intellect, letters, and praiseworthy habits, named Jane.’ (38) Although it is not clear if the author actually saw Jane in person to form this view, or received the details from someone who did. In the context of the letter, Jane’s description refers to an explanation of who she was in dynastic terms.

Dr Stephan Edwards writes that ‘repeated and unsupported fabrications reduce Nine Days’ Queen from the realm of biography to that of historical fiction.’ (39) As with Davey’s account of Jane’s execution, this would also seem to be true regarding some of the details he gives about Jane’s wedding. He embellishes the accounts by Commendone, ‘by the insistence of her mother’, (40) and Rosso, ‘urged by the mother’ (41), so that ‘the broad red face of the Lady Frances purpled threateningly.’ (42) Again he has used details from the ‘Spinola letter’ and in repeating Burke’s description, even though he admits that Burke does not name his source, the very act of including it, further blurs the line between fact and fiction about what we know of Jane.

Sources

1.De Lisle, L. (2010), ‘Faking Jane’, BBC History Magazine, March.

De Lisle, L. (2010) The Sisters Who Would Be Queen: The Tragedy of Mary, Katherine and Lady Jane Grey, HarperPress, p.113

De Lisle, L. (2014), Tudor: The Family Story, Vintage, p.269-270

2.Edwards, S. (2015), A Queen of a New Invention: Portraits of Lady Jane Grey Dudley, England’s ‘Nine Days Queen’, Old John Publishing, p.177.

3.Edwards, S. (2015), A Queen of a New Invention: Portraits of Lady Jane Grey Dudley, England’s ‘Nine Days Queen’, Old John Publishing, p.180.

4.Hills, T. (2015), ‘Lady Jane Grey’s Death and Burial’, Tudor Life Magazine, February.

5.Davey, R. (1909) The Nine Days’ Queen: Lady Jane and Her Times, Methuen & Co, p.230.

6.Ibid.

7.Edwards, S. Historia delle cose occorse nel regno d’Inghilterra – An Introduction to this Source Date accessed: 30 December 2015.

8.Ibid.

9.Ibid.

10.Edwards, S. HISTORY OF THE EVENTS [that] OCCURRED IN THE REALM OF ENGLAND in relation to the Duke of Northumberland after the death of Edward VI. – Date accessed: 30 December 2015.

11.Ives, E. (2009) Lady Jane Grey: A Tudor Mystery, Wiley-Blackwell, p.29.

12.Malfatti, C.V (translator) (1956), The Accession Coronation and Marriage of Mary Tudor as related in four manuscripts of the Escorial, Barcelona, p.5.

13.Edwards, S. Two Letters Concerning Lady Jane Grey of England, written in London in July of 1553 Date accessed: 30 December 2015).

14.Ibid.

15.Ibid.

16.De Lisle, L. Leanda de Lisle Blog Date accessed: 30 December 2015.

17.Ibid.

18.Ives, E. (2009) Lady Jane Grey: A Tudor Mystery, Wiley-Blackwell, p.107 and 321

19.Diarmaid Macculloch (1984). III The Vita Mariae Angliae Reginae of Robert Wingfield of Brantham. Camden Fourth Series, 29, p.245.

20.Davey, R. (1909) The Nine Days’ Queen: Lady Jane and Her Times, Methuen & Co, p.230.

21.De Lisle, L. (2010) The Sisters Who Would Be Queen: The Tragedy of Mary, Katherine and Lady Jane Grey, HarperPress, p.69.

22.Davey, R. (1909) The Nine Days’ Queen: Lady Jane and Her Times, Methuen & Co, p.233-4.

23.Ibid, p.235.

24.Ibid.

25.Ives, E. (2009) Lady Jane Grey: A Tudor Mystery, Wiley-Blackwell, p.185

26.‘Spain: May 1553’, Calendar of State Papers, Spain, Volume 11: 1553 (1916), pp. 37-48. URL: http://www.british-history.ac.uk/report.aspx?compid=88480 Date accessed: 30 December 2015.

27.Ibid.

28.Edwards, S. Two Letters Concerning Lady Jane Grey of England, written in London in July of 1553 Date accessed: 30 December 2015).

29.Ives, E. (2009) Lady Jane Grey: A Tudor Mystery, Wiley-Blackwell, p.185

30.Strype, J. Ecclesiastical Memorials Relating Chiefly to Religion and the Reformation of It, and the Emergencies of the Church of England Under K. Henry VIII., K. Edward VI., and Q. Mary I., with Large Appendices Containing Original Papers Google Books, p.111-112. Date accessed: 30 December 2015

31.Burke, S. Hubert. (2013). pp. 472-3. Historical Portraits Of The Tudor Dynasty and the Reformation Period (Vol. 2). London: Forgotten Books. (Original work published 1880). http://www.forgottenbooks.com/readbook_text/Historical_Portraits_Of_The_Tudor_Dynasty_and_the_Reformation_Period_v2_1000348868/483 p.472 Date Accessed: 30 December 2015.

32.Davey, R. (1909) The Nine Days’ Queen: Lady Jane and Her Times, Methuen & Co, p.234.

33.Ibid, p.253

34.Spain: July 1553, 1-10’, Calendar of State Papers, Spain, Volume 11: 1553 (1916), pp. 69-80. URL: http://www.british-history.ac.uk/report.aspx?compid=88483 Date accessed: 30 December 2015. ‘Spain: July 1553, 16-20’, Calendar of State Papers, Spain, Volume 11: 1553 (1916), pp. 90-109. URL: http://www.british-history.ac.uk/report.aspx?compid=88485 Date accessed: 30 December 2015.

‘Diary: 1553 (Jul – Dec)’, The Diary of Henry Machyn: Citizen and Merchant-Taylor of London (1550-1563) (1848), pp. 34-50. URL: http://www.british-history.ac.uk/report.aspx?compid=45512 Date accessed: 30 December 2015.

Edwards, S. Two Letters Concerning Lady Jane Grey of England, written in London in July of 1553 Date accessed: 30 December 2015.

35.Nichols, J. G (ed) (1850) The Chronicle of Queen Jane and of Two Years of Queen Mary and Especially of the Rebellion of Sir Thomas Wyat, Written by a Resident in the Tower of London, Llanerch Publishers, p.32

36.Ibid, p.24-6.

37.Ibid, p.56.

38.Edwards, S. Two Letters Concerning Lady Jane Grey of England, written in London in July of 1553 Date accessed: 30 December 2015).

39.Edwards, S. (2015), A Queen of a New Invention: Portraits of Lady Jane Grey Dudley, England’s ‘Nine Days Queen’, Old John Publishing, p.180.

40.Malfatti, C.V (translator) (1956), The Accession Coronation and Marriage of Mary Tudor as related in four manuscripts of the Escorial, Barcelona, p.5.

41.Edwards, S. HISTORY OF THE EVENTS [that] OCCURRED IN THE REALM OF ENGLAND in relation to the Duke of Northumberland after the death of Edward VI. – Date accessed: 30 December 2015.

42.Davey, R. (1909) The Nine Days’ Queen: Lady Jane and Her Times, Methuen & Co, p.230.