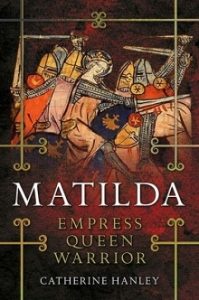

Catherine Hanley is the author of ‘Matilda: Empress, Queen, Warrior’ which was published by Yale University Press last month.

Catherine is also the author of ‘Louis: The French Prince Who Invaded England’ and a five part historical fiction medieval mystery series written under the name C.B. Hanley (The Sins of the Father, The Bloody City, Whited Sepulchres, Brother’s Blood and Give Up The Dead).

Buy ‘Matilda: Empress, Queen, Warrior’:

Follow Catherine on Social Media:

Catherine’s website: Catherine Hanley – Historian and Author

Twitter: @CathHanley

Many thanks to Catherine for answering my questions.

Why did you choose this subject for your book?

A combination of reasons, really. My academic background is in twelfth- and thirteenth-century warfare, but I was increasingly aware that I was mainly writing about men, and that it might be nice to write something about a woman for a change! With Matilda I could do this while still having a good dollop of war and combat included, so the subject fitted quite well. And on top of that, I’ve always felt that Matilda’s extraordinary life and actions have never been properly recognised or appreciated, so there was an element of being able to bring forward this great story to a new audience.

What does your book add to existing works about Matilda?

Obviously there have been some fantastic academic studies of Matilda in the past – I could never hope to surpass Marjorie Chibnall’s The Empress Matilda for depth – but I was hoping to achieve two things. Firstly, to take advantage of the great strides that have been made in medieval gender and queenship studies over the last two decades, to present a new viewpoint on Matilda; and secondly, to write about her in (what I hope is) a more user-friendly way so that readers don’t feel that they need to have a whole lot of background knowledge already before they can pick the book up.

What surprised you most researching this book?

Just how much responsibility Matilda had at such a young age. Some of it makes quite horrendous reading these days: sent abroad for a betrothal, away from her family (she never saw her mother or her brother again) and to a foreign-speaking land, when she was just eight years old; married before she was twelve. But she turned this adversity to her advantage, and by the time she was sixteen she was ruling Italy as her husband’s regent.

If Matilda had been in London when Henry I died, do you think she would have become Queen or were attitudes towards female rule too impossible to overcome?

Good question. One of the reasons Stephen was able to take the throne is that he was in possession of the all-important information much sooner than Matilda was: he had crossed the Channel, secured the treasury and had himself crowned before Matilda even knew Henry was dead. And once he had been crowned, that was it – a fait accompli. If Matilda had been in London it is probable that Stephen would not have been able to carry out this unexpected lightning manoeuvre. There would have been time for more discussion, more reflection involving more nobles, about who should succeed Henry. In short, I certainly think that it might have delayed matters, and made Matilda’s candidacy more of a subject for discussion, but I’m not sure if the result would have been any more favourable. Stephen might not have been chosen as king, but it doesn’t necessarily follow that Matilda would have been, either.

Why was Matilda condemned for behaving like a King while Queen Matilda (wife of Stephen) was praised for being ‘a woman…of a man’s resolution?’ (p.155)

At this time, women were routinely expected to bear great responsibility: administering and defending great estates, entering into negotiations, and so on. But the crucial point was that any authority they had was strictly confined within male power structures: all of these actions were acceptable only if a woman was acting on behalf of her husband, her son, etc. What disturbed contemporaries so much was that Matilda was seeking to rule on her own, in her own right: she had a husband and a son but they were not mentioned in her claim – she sought the crown for herself, and this was considered unacceptable. Queen Matilda, on the other hand, raised an army and took action specifically on behalf of her husband when he was imprisoned, so this was seen in a very different light. And, of course, once Stephen was free, his wife did the appropriate womanly thing and stepped back into the background. Thus she could be praised and Matilda condemned, even though their actions were very similar.

What was Stephen’s greatest mistake as King?

Basically, seizing the crown in the first place. It proved relatively easy to obtain and very difficult to keep – and there was a lot more to kingship than just having the crown put on your head, as he soon discovered once it was too late to back out. He made one snap decision and then spent the rest of his life trying to live up to it, barely knowing a day’s peace. By the time he died he had lost his wife and his eldest son, and the trust of many of his friends, and I wonder whether he thought it was all worth it.

What was Matilda’s greatest triumph?

Seeing her son inherit the throne. By the time Stephen had been king for a decade, it was clear that the war over who would succeed Henry I was over. It might have been easy for Matilda to give up, but there was still a war to be fought over who would succeed Stephen, and she was utterly determined that it would be her son rather than his.

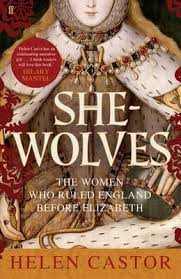

What do you think had changed between Matilda’s challenge for the throne and the successful challenge of Mary I?

Sixteenth-century England was still a deeply patriarchal society, and one might argue that little had changed. However, Mary did have one tremendous advantage over Matilda, in that all the other candidates for the throne after Edward VI’s death were also female – her struggle was not one of gender per se, but rather of religion and hereditary preference (caveat: I am by no means a Tudor expert and there is no doubt a lot more to it than that!). Having said that, once Mary did accede, she – and her sister Elizabeth after her – were able to turn the tables and use gender stereotypes to their advantage in a way that the more direct Matilda either never considered or never allowed herself to do.