‘Medieval Women: In Their Own Words’ opened at the British Library on 25th October 2024 and runs until 2nd March 2025.

It is a fabulous exhibition and worth every penny! I have seen it twice.

‘Medieval women’s voices evoke a world in which they lived active and varied lives. Their testimonies speak of diverse experiences, revealing female impact and influence across private, public and spiritual realms, and bringing alive experiences that still resonate today.

This exhibition focuses on Europe from roughly 1100 to 1500, a period in which there was strong cultural interconnection across the continent. While most medieval sources from the period were written by and about men, women’s surviving testimonies offer remarkable insight into their contributions to medieval social and economic life, culture and politics, their skilful management of households and convents, and the vibrancy of female religious culture.

This is the story of medieval women, told in their own words.’

My highlights of the exhibition included:

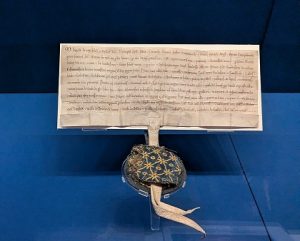

Foundation charter of Bordesley Abbey for Empress Matilda Devizes, Wiltshire (England), 1141-42

‘Matilda almost became the first ruling queen of England. After her father, King Henry I, died and her cousin Stephen seized the throne, Matilda opposed Stephen in a civil war. For a brief period in the 1140s, while King Stephen was in prison, Matilda in effect ruled England in her own right. In this document Matilda is styled ’empress’ and ‘lady of the English.’ It’s seal depicts her crowned and holding a sceptre, and the silk seal bag may have been fashioned from one of her dresses.’

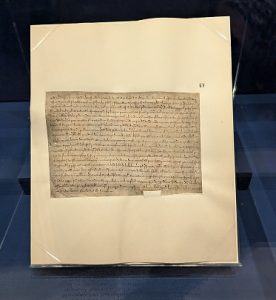

Close Roll recording a debt owed to Licoricia of Winchester England, 1234

‘This is the earliest documented reference to Licoricia of Winchester, perhaps the most successful Jewish businesswoman in medieval England. She is first recorded lending money in 1234, as a widow, and in time she became one of King Henry III’s chief financiers. In 1277, Licoricia was murdered at her home in Winchester, along with Alice of Bickton, her Christian maidservant. it was almost certainly an antisemitic crime, but no one was ever convicted, despite her sons having identified the assailants.’

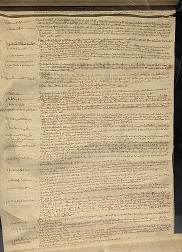

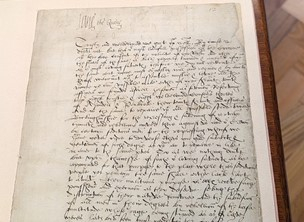

Letter of William Fraser, bishop of St Andrews, to King Edward I

Scotland, 7 October 1290

‘In 1290, a seven-year-old girl set sail from Norway, her homeland, to Scotland. Margaret, maid of Norway, had inherited the title Queen of Scots when her grandfather died in 1286. She was supposed to marry Prince Edward of England (the future Edward II), uniting the two kingdoms. But Margaret never arrived. On 7 October, the Bishop of St Andrews informed King Edward I that Margaret had died en route, perhaps in Orkney; she never set foot on the Scottish mainland.’

Seal impression of Isabella of France

England, 1308-1358

‘This rare original seal impression would once have been attached to a document that Isabella issued…Her crown, sceptre and ermine-lined cloak are emblems of royalty and majesty, the coats of arms of England and France represent her distinguished marriage and ancestry, while the post with her hand on her breast denotes sincerity and humility.’

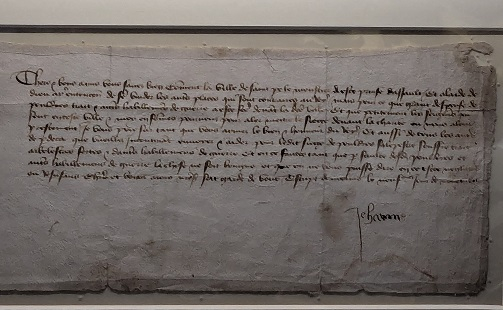

Letter from Joan of Arc to the citizens of Riom Moulins (France)

9 November 1429

‘When Joan of Arc sent this letter to the citizens of Riom, she was planning to besiege the town of La-Charite-sur-Loire but her army’s supplies were running low. She entreated the city to assist by sending gunpowder and military equipment.

Being illiterate, Joan dictated her letter to a scribe, but signed her own name, ‘Jehanne’, at the end. This is the earlies of three surviving examples of Joan’s signature, her large uncertain letter forms suggesting her unfamiliarity with writing.’

‘The Talbot Shrewsbury Book’

Rouen (France), around 1444-45

‘During 1444 to 1445, Margaret of Anjou was escorted from France to England in great splendour for her marriage to Henry VI. She received this sumptuous collection of romances and chivalric treatises as a wedding gift from John Talbot, Earl of Shrewsbury and one of Henry’s senior commanders in France. The opening miniature shows Talbot presenting the book to Margaret who sits enthroned with Henry.’

The Foundress’ Cup

England, 15th century

‘Eleanor Cobham shocked medieval English society when in 1428 she married Humfrey, Duke of Gloucester, one of the most powerful men in the kingdom. Eleanor and Humfrey shared a love of high living, culture and learning. This silver-gilt cup, one of the finest surviving examples of 15th-century English metalwork, her their joint coat of arms enamelled inside. This suggests that it was originally made for them, providing a glimpse of the splendour of their life together. The cup was later bequeathed to Christ’s College, Cambridge, y Lady Margaret Beaufort in 1507.’

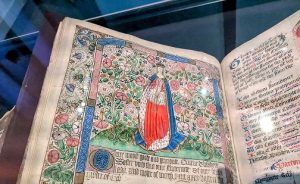

Book of the Fraternity of the Assumption of Our Lady London (England), 1475

‘This image of Elizabeth Woodville, Queen of England as the wife of Edward IV, marks her admission to the confraternity (a religious and charitable association) of the London Skinners (traders in animal furs). By honouring her in this way, the Skinners were perhaps hoping to cultivate Elizabeth as a potential mediator on their behalf. In 1479, Elizabeth interceded with the king on behalf of the London Mercers (cloth merchants) over subsidy payments they owed, and eventually thanks to ‘the queen’s good grace’ Edward eased his demands.’

Portrait of Margaret of York

modern-day Belgium, around 1468

‘Margaret of York (d.1503), Duchess of Burgundy, was renowned for her patronage of books, education and religion. The sister of Edward IV of England, she married Charles the Bold (d. 1477), Duke of Burgundy, in 1468. This portrait was probably painted soon after her marriage. The gold ‘B’ pin on her headdress signifies Burgundy, while the alternating letters ‘C’ and ‘M’ on her necklace stand for ‘Charles’ and ‘Margaret.’

Miroir des dames (Mirror of Ladies)

France, 1428

‘This treatise on queenship was originally written in Latin for Jeanne I, queen of Navarre (d.1305), by her confessor, Durand de Champagne, who are both depicted on the right-hand page. Drawing on the scriptual verse ‘A wise women buildeth her house’ (Proverbs 14:1), the text describes how a queen must metaphorically fortify her exterior house (her conscience). On the left-hand page is the coat of arms of Henry VII of England, who perhaps had this copy for the education of his daughters.’